Hollow Bones & Air Sacs: The Respiratory Secrets of Dinosaurs, Revealed

Imagine standing in the shadow of an Argentinosaurus, a creature so immense its vertebrae were the size of armchairs. Or picture a Tyrannosaurus rex in full pursuit, a nine-ton predator thundering across the Cretaceous landscape. A single question looms as large as the dinosaurs themselves: How did they breathe? How did they power such colossal bodies and fuel such active lifestyles?

The answer is not simply in their lungs. The true secret lies deep within their skeletons, in a revolutionary biological design that made them lighter, more efficient, and ultimately, rulers of their world. It’s a story of hollow bones and an intricate, unseen network of internal air sacs—a respiratory system more akin to that of a modern hummingbird than a modern lizard.

The “Hollow” Truth: More Than Just Empty Space

When we hear the word “hollow,” we might think of something empty or lacking substance, as dictionaries define it: “having a space or cavity inside; not solid.” Early paleontologists who discovered the curiously light and cavernous bones of certain dinosaurs might have been similarly perplexed. But these bones were far from simply empty. They were a marvel of evolutionary engineering.

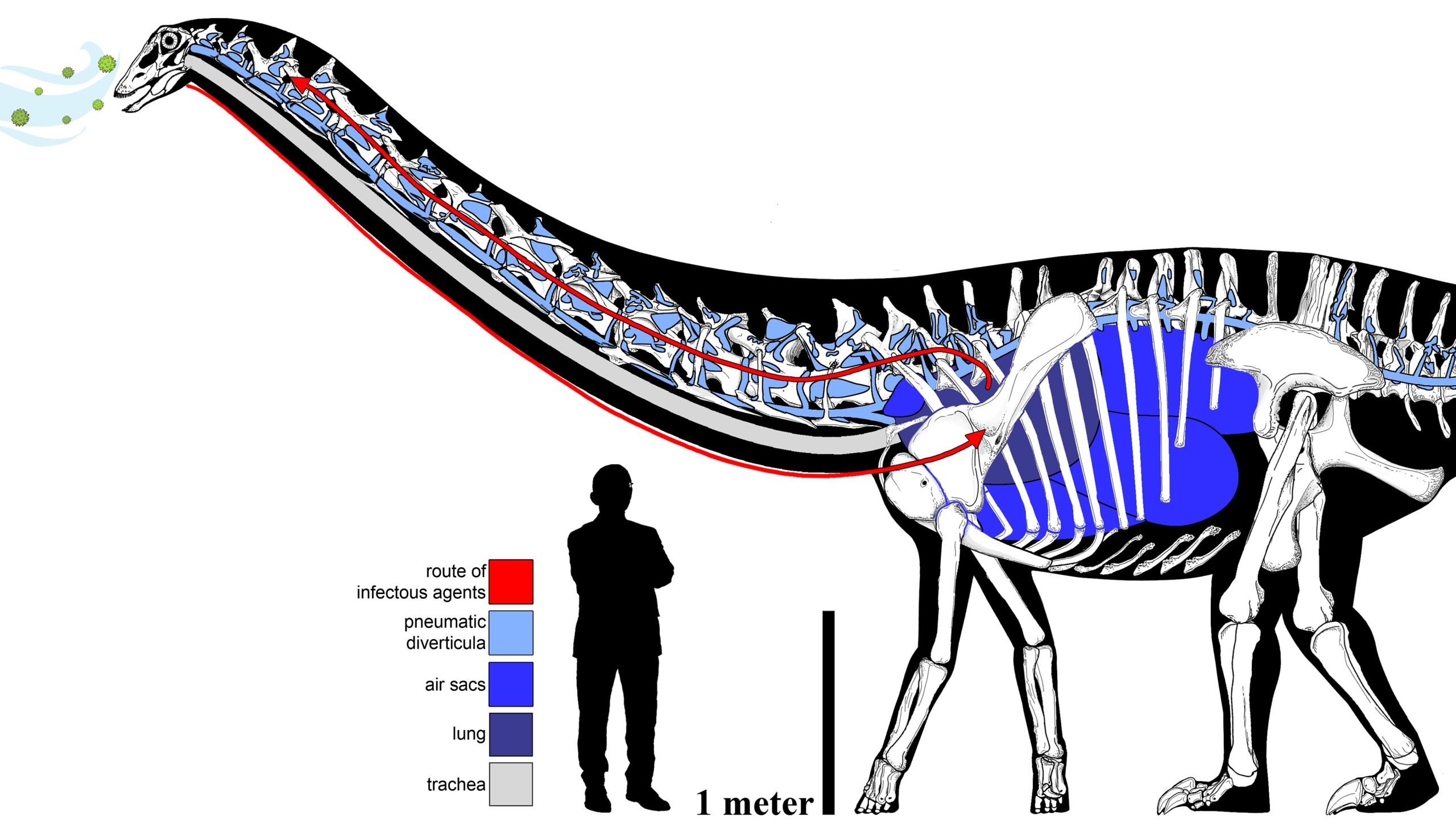

This feature, known as skeletal pneumaticity, refers to the presence of air-filled spaces within bones. In dinosaurs, particularly the Saurischian group (which includes two-legged theropods like T. rex and long-necked sauropods like Brachiosaurus), these were not just hollow tubes. They were honeycombed with cavities and openings, called pneumatic foramina. These weren’t signs of weakness; they were connection points. They were the physical evidence of a sophisticated respiratory system that extended far beyond the lungs, invading the skeleton itself.

Think of it as an internal network of biological balloons, woven through the vertebrae, ribs, and even limb bones, all connected back to the lungs. This system didn’t just carry air; it fundamentally changed what it meant to be a dinosaur.

The Avian Supercharger: A One-Way Ticket to Efficiency

To understand how this system worked, we need to look at the dinosaurs’ only living descendants: birds. Birds possess the most efficient respiratory system of any vertebrate on the planet, and the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that their non-avian dinosaur ancestors had a very similar, if not identical, setup.

Unlike mammals, whose lungs operate on a tidal, in-and-out breathing pattern, birds and many dinosaurs utilized a unidirectional airflow. Air flows in a single, continuous loop through the lungs, thanks to a series of air sacs.

Here’s how it works:

- First Inhalation: Air is drawn into the posterior (rear) air sacs.

- First Exhalation: This fresh air is pushed from the posterior sacs into the lungs, where gas exchange (oxygen in, carbon dioxide out) occurs.

- Second Inhalation: Stale air from the lungs is drawn into the anterior (front) air sacs, while a new breath of fresh air refills the posterior sacs.

- Second Exhalation: The stale air in the front sacs is expelled, while fresh air from the rear sacs moves into the lungs.

The result? The lungs receive a constant, one-way stream of fresh, oxygen-rich air during both inhalation and exhalation. This system is a biological supercharger, wringing every last molecule of oxygen from each breath.

Breathing Systems: A Tale of Two Designs

| Feature | Mammalian ‘Tidal’ Breathing | Avian/Dinosaur ‘Flow-Through’ Breathing |

|---|---|---|

| Airflow | Two-way (in & out) | One-way (unidirectional) |

| Efficiency | Good | Exceptional |

| Lungs | Spongy, expandable sacs | Rigid, honeycombed structures |

| Secret Weapon | Diaphragm muscle | A network of air sacs |

| Result | Fresh & old air mix | Lungs get 100% fresh air |

The Advantages of a Hollow Core

This incredibly complex system wasn’t just an evolutionary novelty; it provided a suite of powerful advantages that were critical to the dinosaurs’ success.

-

Lightening the Colossal Load: For a sauropod with a neck longer than a school bus, the weight of a solid skeleton would have been crushing. By hollowing out the massive vertebrae and filling them with lightweight air, pneumaticity drastically reduced skeletal weight—by some estimates, a sauropod skeleton was 10-15% lighter than if it were solid. This made movement possible and saved an immense amount of energy.

-

Fuel for the Fire: The super-efficient oxygen uptake of the flow-through respiratory system was perfect for fueling a high metabolism. This lends strong support to the idea that many dinosaurs were active, warm-blooded (endothermic) animals, not sluggish, cold-blooded reptiles. It provided the power for a T. rex to chase down prey and a Velociraptor to perform agile, energetic attacks.

-

A Built-in Cooling System: A multi-ton animal generates a tremendous amount of internal heat. Overheating would have been a constant danger. The vast network of air sacs, extending deep into the body’s core, would have acted as a remarkable internal cooling system. The constant flow of air through the body could have dissipated excess heat, much like a radiator in a car.

Reading the Bones: How We Know What We Know

This incredible picture of dinosaur breathing isn’t science fiction; it’s the result of decades of meticulous detective work. Paleontologists have pieced together the evidence from multiple lines of inquiry:

-

Fossil Evidence: The most direct proof comes from the bones themselves. The distinct openings, cavities, and internal textures (pneumatic foramina) on fossilized vertebrae are identical in form and function to those found in modern birds. By mapping these features, scientists can reconstruct the likely size and placement of the air sacs.

-

Advanced Imaging: Modern technology has revolutionized paleontology. CT scanners and digital modeling allow scientists to peer inside priceless fossils without ever cutting them open. These scans reveal the intricate, honeycomb-like internal structures that confirm the presence of extensive pneumaticity.

-

Comparative Anatomy: The link between birds and dinosaurs is one of the strongest theories in paleontology. By studying the respiratory system of birds—from ostriches to eagles—we gain a living, breathing blueprint for how their ancient theropod ancestors likely functioned.

The Echo of a Prehistoric Breath

The hollow bones and air sacs of dinosaurs were not just a curious feature; they were the key to their evolutionary supremacy. This sophisticated respiratory system allowed them to overcome the physical constraints of size, to power active, high-energy lifestyles, and to dominate virtually every terrestrial ecosystem on Earth for over 150 million years.

It’s a powerful reminder that some of the greatest secrets in the history of life are hidden in plain sight. The next time you watch a pigeon take flight or hear a sparrow sing, listen closely. You might just be hearing the echo of a prehistoric breath—a biological legacy that has powered the giants of the past and the masters of the air today.

Additional Information

Of course. Here is a detailed article and analysis on the respiratory system of dinosaurs, incorporating the provided dictionary definitions to clarify the foundational concept of “hollow” bones.

Revealed: The Avian Lungs and Hollow Bones that Fueled the Dinosaurs

For over a century, dinosaurs have captured our imagination as colossal, powerful beasts that dominated the prehistoric world. But one of the most profound secrets to their success lay hidden within their very skeletons—a revolutionary respiratory system that was far more sophisticated than our own and is still used by their living descendants: birds. This system of hollow bones and air sacs didn’t just allow them to breathe; it enabled their gigantism, fueled their high-energy lifestyles, and gave them an evolutionary edge for millions of years.

1. The Meaning of “Hollow”: More Than Just Empty Space

To understand this system, we must first start with the bones themselves. The term “hollow” is key. As defined by leading dictionaries like Merriam-Webster, Cambridge, and Dictionary.com, hollow means “having a space or cavity inside; not solid; empty.” This accurately describes the basic structure of these dinosaur bones. They were not filled with heavy marrow like our own.

However, in paleontology, this “hollowness” signifies something far more complex than simple emptiness. These bones were pneumatized, meaning they were filled with air. They were invaded by extensions of the respiratory system known as air sacs, creating a network of struts and air pockets that made the skeleton incredibly strong yet remarkably lightweight. The evidence for this is found in the fossils themselves: small openings on the bone surface called pneumatic foramina, which are the tell-tale entry points where the air sacs connected to the bone’s interior.

2. The Avian Blueprint: A One-Way Street for Air

To grasp how this system worked, we look to modern birds. Mammals, including humans, have a “tidal” respiratory system. We inhale air into our lungs, and then we exhale it back out the same way. This is inefficient because fresh, oxygen-rich air is constantly mixing with stale, carbon dioxide-rich air that remains in the lungs.

Dinosaurs, particularly the theropods (like T. rex) and sauropods (like Brachiosaurus), shared the same advanced system as birds: a unidirectional, flow-through respiratory system. It functions like a one-way street, ensuring that a constant stream of fresh, highly-oxygenated air flows over the lungs. This is accomplished through a network of air sacs that act as bellows, storing air and pumping it through the rigid lungs.

The process required two full breath cycles to move one pocket of air completely through the system:

- Inhalation 1: Fresh air is drawn into the body, bypassing the lungs and filling the posterior (rear) air sacs.

- Exhalation 1: The posterior air sacs contract, pushing this fresh air into the lungs, where gas exchange (oxygen in, carbon dioxide out) occurs.

- Inhalation 2: As the next breath of fresh air is drawn into the posterior sacs, the now-stale air from the lungs is pushed into the anterior (front) air sacs.

- Exhalation 2: The anterior air sacs contract, expelling the stale, carbon dioxide-rich air from the body.

This ingenious cycle means the lungs are almost continuously bathed in fresh, oxygenated air, making it vastly more efficient than the mammalian system.

3. The Evolutionary Advantages: Why This System Was a Game-Changer

This hyper-efficient respiratory system provided dinosaurs with several incredible advantages that were key to their evolutionary dominance.

-

Fuel for a High Metabolism: This system supplied the enormous amounts of oxygen needed to sustain a high metabolism. This supports the modern view of many dinosaurs as active, energetic, and likely warm-blooded animals, rather than the slow, lumbering reptiles of early theories. A predator like Velociraptor or Tyrannosaurus rex would have needed this efficiency to hunt and chase down prey.

-

Enabling Gigantism: A skeleton made of solid bone would have been crushingly heavy for the largest dinosaurs. The pneumatized, hollow bones of a sauropod like Argentinosaurus drastically reduced its body weight. This light-but-strong skeletal framework was a critical prerequisite for evolving to such colossal sizes. Without hollow bones, a 100-ton sauropod might have been a biological impossibility.

-

An Internal Cooling System: The air sacs, which extended throughout the body cavity and into the bones, also acted as a sophisticated internal cooling mechanism. For massive animals generating immense metabolic heat, this system would have been vital for dissipating that heat and preventing overheating, much like a car’s radiator.

-

Adaptability to Low-Oxygen Environments: During parts of the Mesozoic Era, atmospheric oxygen levels may have been lower than they are today. A respiratory system that could extract oxygen from the air with extreme efficiency would have given dinosaurs a significant survival advantage over other animals with less effective tidal breathing systems.

4. Evidence in the Fossil Record: The Smoking Gun

This theory isn’t just speculation; it is firmly rooted in fossil evidence. Paleontologists can identify pneumatized bones across a wide range of dinosaur groups.

- Theropods: The lineage leading to birds, including Allosaurus and T. rex, shows extensive pneumatization in their vertebrae, ribs, and even pelvic bones.

- Sauropods: The long-necked giants have the most extreme examples. Their neck vertebrae are often more than 50% air by volume, making their famously long necks physically possible to lift and support.

- Pterosaurs: While not technically dinosaurs, these flying reptiles had an almost identical system, which was essential for the high-energy demands of powered flight.

Modern technologies like CT scanning have allowed scientists to peer inside these fossils non-destructively, creating 3D models of the intricate internal air chambers and confirming the presence of this avian-style system.

Conclusion: Breathing Life into Our Image of Dinosaurs

The discovery of the dinosaurs’ respiratory secrets has fundamentally changed our understanding of them. The “hollow bones,” far from being a sign of fragility, were the hallmark of a sophisticated biological machine. This system reveals dinosaurs not as primitive reptiles, but as dynamic, highly-active, and incredibly well-adapted creatures. It is a powerful reminder that the birds we see today are living dinosaurs, carrying with them the same respiratory blueprint that allowed their ancient ancestors to rule the Earth.